Web Fundamentals

Client and Servers

Client-Server Model

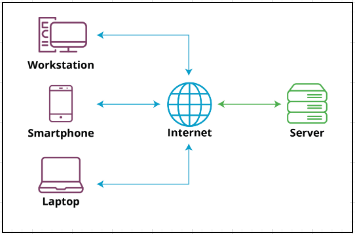

The client-server model is a computing architecture that separates the functions of a computer program into two essential components: the client, which makes requests, and the server, which fulfills those requests.

-

Clients

- Devices (e.g., computers, smartphones) that access the internet and make requests.

- Common browsers include Chrome, Safari, and Edge.

-

Servers

- Specialized hardware designed to host web applications and websites.

- Respond to client requests and provide the necessary information.

Key Differences:

- Functionality: Clients make requests; servers fulfill requests.

- Software: Servers run web service software; clients use browsers.

- Power: Servers are more powerful, designed to handle concurrent requests.

- Specialization: Servers are dedicated to hosting and responding to requests.

Accessing Websites

To access specific websites, a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) is used. The URL is a web address that directs the browser to a specific resource on the internet.

Components of a URL:

- Protocol: Indicates the method of access, such as HTTP or HTTPS.

- Domain Name: The main address of the website (e.g., www.example.com).

- Path: Specifies the exact resource or page on the website (e.g., /about-us).

Example:

- URL:

https://www.example.com/about-us - Protocol: HTTPS

- Domain Name: www.example.com

- Path: /about-us

The URL tells the browser where to find the resource, and the browser uses the protocol to establish the type of connection.

Request-Response Cycle

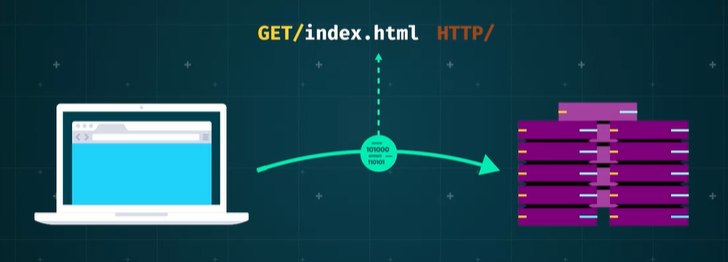

The request-response cycle is a fundamental process that describes how clients and servers communicate over the internet.

-

Client Request:

- The client makes a request by entering a URL in the browser.

- The browser sends an HTTP request to the server hosting the website.

-

Server Response:

- The server processes the request.

- It sends back the requested information, typically in the form of a web page, to the client.

-

Displaying Information:

- The browser receives the response and renders the web page for the user.

This cycle is repeated for each new request made by the client, enabling seamless browsing and interaction with web applications.

Server Software

Server software plays a critical role in handling and responding to client requests. This software is designed to manage web traffic, process requests, and deliver content efficiently.

Examples of Server Software:

-

Apache HTTP Server:

- One of the most popular web server software.

- Known for its flexibility and wide usage.

-

Nginx:

- High performance, can handle a large number of simultaneous connections.

-

Microsoft IIS (Internet Information Services):

- A web server software for Windows Server.

- Offers a robust platform for hosting web applications.

Servers run this software to handle HTTP requests from clients, ensuring that web pages and resources are delivered promptly and reliably.

Handling Demand

Popular websites, like Google.com, face high demand, requiring exceptionally powerful servers to manage the influx of requests. While any computer could be set up as a server, dedicated servers are often highly specialized for performance.

URLs

Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) are essential for the web's hypertext system. They provide the information a browser needs to send a request to a server and specify the desired resource. URLs are divided into two main parts separated by a colon: the scheme and the path.

-

Scheme: Specifies the protocol the browser should use to retrieve the resource. Examples include:

- HTTP

- HTTPS

- FTP

- Email protocols like POP3 and IMAP

-

Path: Provides the location of the server and the specific resource.

Example URL

https://www.qa.com/web-development-fundamentals-html-and-css-qahtmlcss

Where:

- Scheme: HTTPS

- Path: www.qa.com/web-development-fundamentals-html-and-css-qahtmlcss

Simplified URL Entry

When entering URLs into browsers, it's common not to type the scheme. Browsers often add the default scheme (usually HTTP or HTTPS) automatically.

As common practice, many users omit the scheme (HTTP or HTTPS) when entering URLs directly into browsers. This simplifies the entry process and is commonly seen when typing addresses like www.qa.com instead of specifying http://www.qa.com explicitly.

Browsers will then automatically prepend the default scheme (typically HTTP or HTTPS) if it's omitted. This practice reduces the burden on users to remember and type out the full URL scheme.

HTTP URL Syntax

HTTP and HTTPS URLs have their own syntax, which includes the hostname, port, and document path.

Syntax:

hostname:port/document-path

where:

-

Hostname:

- Represents the name of the accessed website.

- Commonly starts with "www," but this is not mandatory.

-

Port:

- Follows the hostname and may include a port number (e.g., www.example.com:80).

- If no port is specified, HTTP defaults to port 80 and HTTPS to port 443.

-

Document Path:

- The location of the resource in the web service directory.

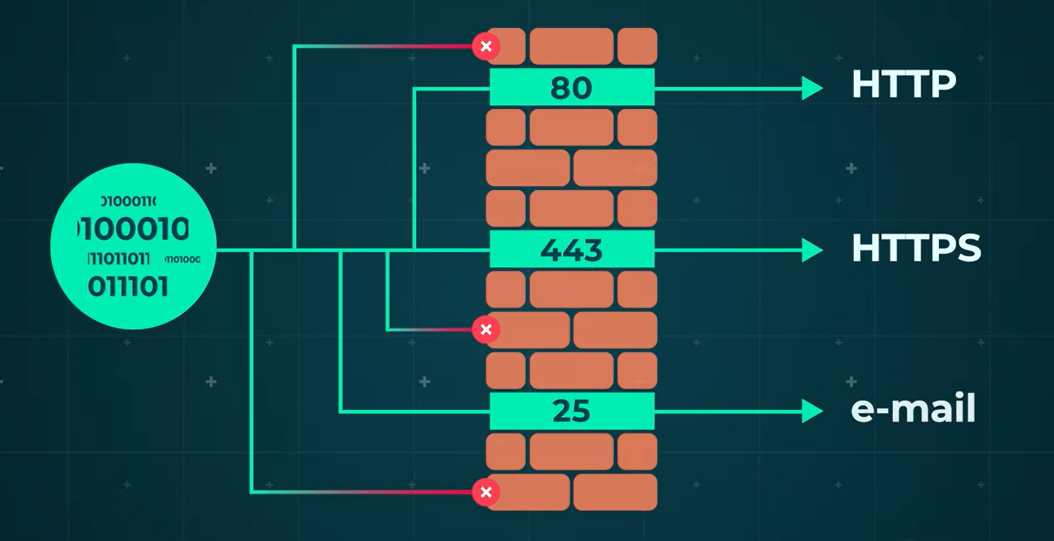

Importance of Port Numbers

Port numbers act as gateways, allowing or rejecting data based on firewall settings. Common port numbers include:

- Port 80: HTTP

- Port 443: HTTPS

- Port 25: Email

Document Path

The document path indicates where the resource is located within the web service directory. If the document path is omitted from the URL, it defaults to the site's home page, which is server and configuration dependent (e.g., index.html or default.html).

HTTP and its Interactions

The client-server model operates under the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP).

- HTTP is a lightweight application-level protocol established in 1990, currently at version 1.1.

- Built on top of the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), HTTP ensures reliable handling of large volumes of data.

- HTTP operates in a stateless manner, treating each request independently without storing persistent information about the client or server.

Despite its simplicity in handling document requests, HTTP presents challenges for applications requiring identity tracking. When a client accesses a website, it sends a request to the server that includes:

- The method of the request (e.g., GET, POST).

- The Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) specifying the resource location.

- The HTTP protocol version.

Additionally, the client may send headers specifying the content type and other metadata relevant to the request.

Upon receiving the request, the server responds to the client with:

- A status line indicating the HTTP protocol version and an internet standard error code, if applicable.

- A message containing the requested resource or an appropriate response.

Request Formats

HTTP defines three primary methods for client requests: GET, HEAD, and POST.

- GET: Retrieves information identified by the URI.

- HEAD: Fetches header information about the URI.

- POST: Submits a stream of information to the URI's identified resource.