Name Resolution

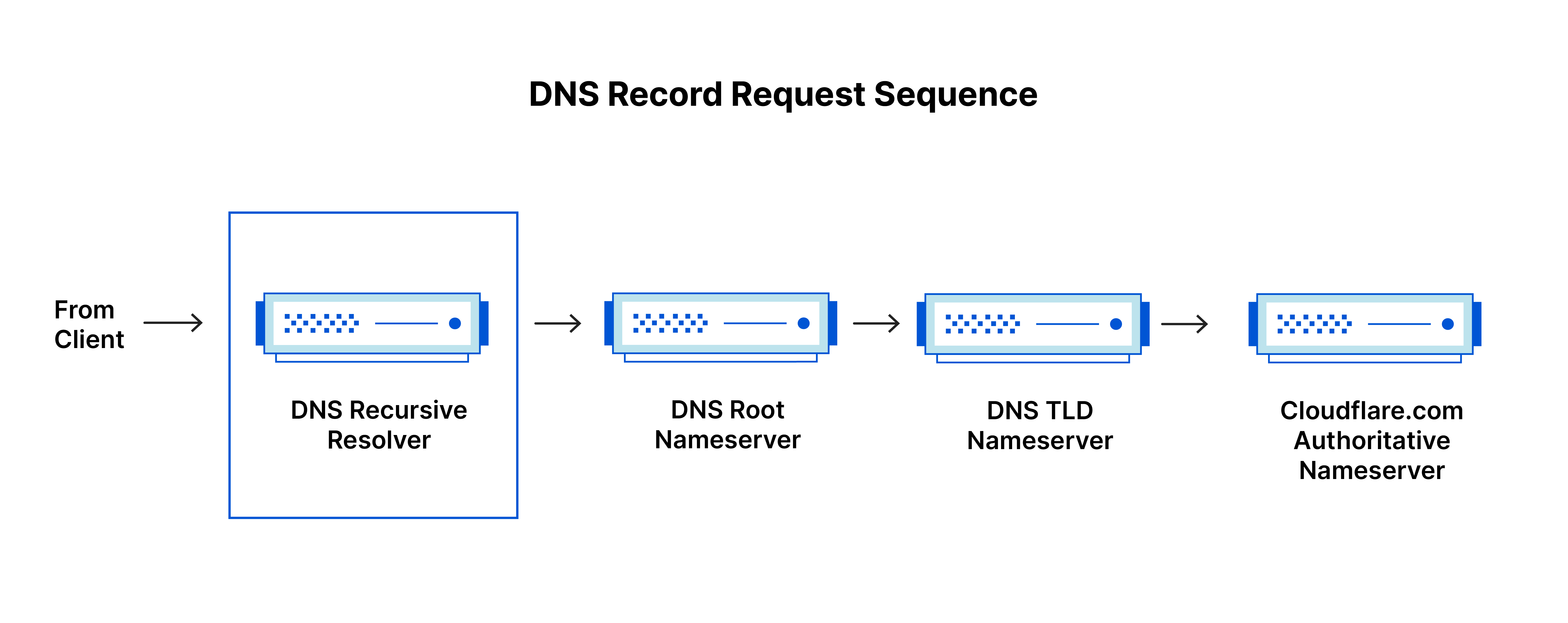

DNS Name Resolution Process

DNS name resolution is the process of finding the IP address for a given domain name.

- User enters a domain name in a browser.

- The system checks the operating system's local DNS cache and host table

- If no record is found, browser sends the request to a DNS resolver.

- The DNS resolver first checks its DNS cache

- The DNS resolver also checks its root hints file

- If no record is found, resolver contacts a root DNS server.

- DNS resolver selects the name servers and sends an iterative query.

- TLD server returns the authoritative server for the domain.

- DNS resolvers sends an iterative query to the authoritative server

- Authoritative server returns the IP address of the domain

- Resolver caches the answer, then sends the IP to the client.

- Client caches the data and passes data to the browser.

- The browser may put the result name in its own cache too.

Local Name Resolution

Local name resolution allows a computer to resolve hostnames to IP addresses without using external DNS servers. It relies on a simple file called the hosts file.

- Works entirely on the local machine

- Uses a hosts file with static IP-to-name mappings

- No root or TLD servers are involved

In Windows, the hosts file is located at

C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\hosts

In Linux:

/etc/hosts

Each line maps an IP address to one or more hostnames. Comments start with # and blank lines are ignored.

Example:

192.168.1.1 home-router

192.168.1.6 home-printer printer

127.0.0.1 localhost

This setup allows you to reach devices by name instead of typing IP addresses. For example:

ping home-router

This resolves to 192.168.1.1 and works immediately without restarting the system.

Common Use Cases

- Small local networks without internet

- Speed up access to frequently used sites by overriding DNS

- Test websites or redirect domains for development

- Basic URL filtering, e.g., mapping a site to

127.0.0.1 - Ensure critical hosts are accessible when DNS is unavailable

Best Practices

- Avoid unnecessary entries to keep lookups fast

- Multiple aliases can share a single IP

- Organize mappings with comments by purpose

- Keep a backup of the hosts file before editing

- Restrict write access to prevent unauthorized changes

DNS Resolvers

DNS resolvers act as the middle layer between a client and the DNS system, helping translate domain names into IP addresses.

- Receive queries from clients for domain resolution

- Check their cache to answer directly if possible

- Contact root servers and follow the resolution path if needed

- Return the final IP address to the client

Resolvers know about root servers through a root hints file, which contains the IP addresses of all root servers. This allows them to start the resolution process for any domain.

Example:

On Windows, you can see your DNS resolver with:

ipconfig /all

On Linux, check the resolver with:

cat /etc/resolv.conf

This shows the IP addresses of resolvers like your router or public DNS services such as Google (8.8.8.8, 8.8.4.4) or Cloudflare (1.1.1.1).

Notes

- Resolvers can be local (like a router) or public (like Google DNS)

- Google DNS resolver is

8.8.8.8and8.8.4.4 - Some support features like EDNS0 or negative caching

- Resolver selection methods may vary: lowest latency or random choice

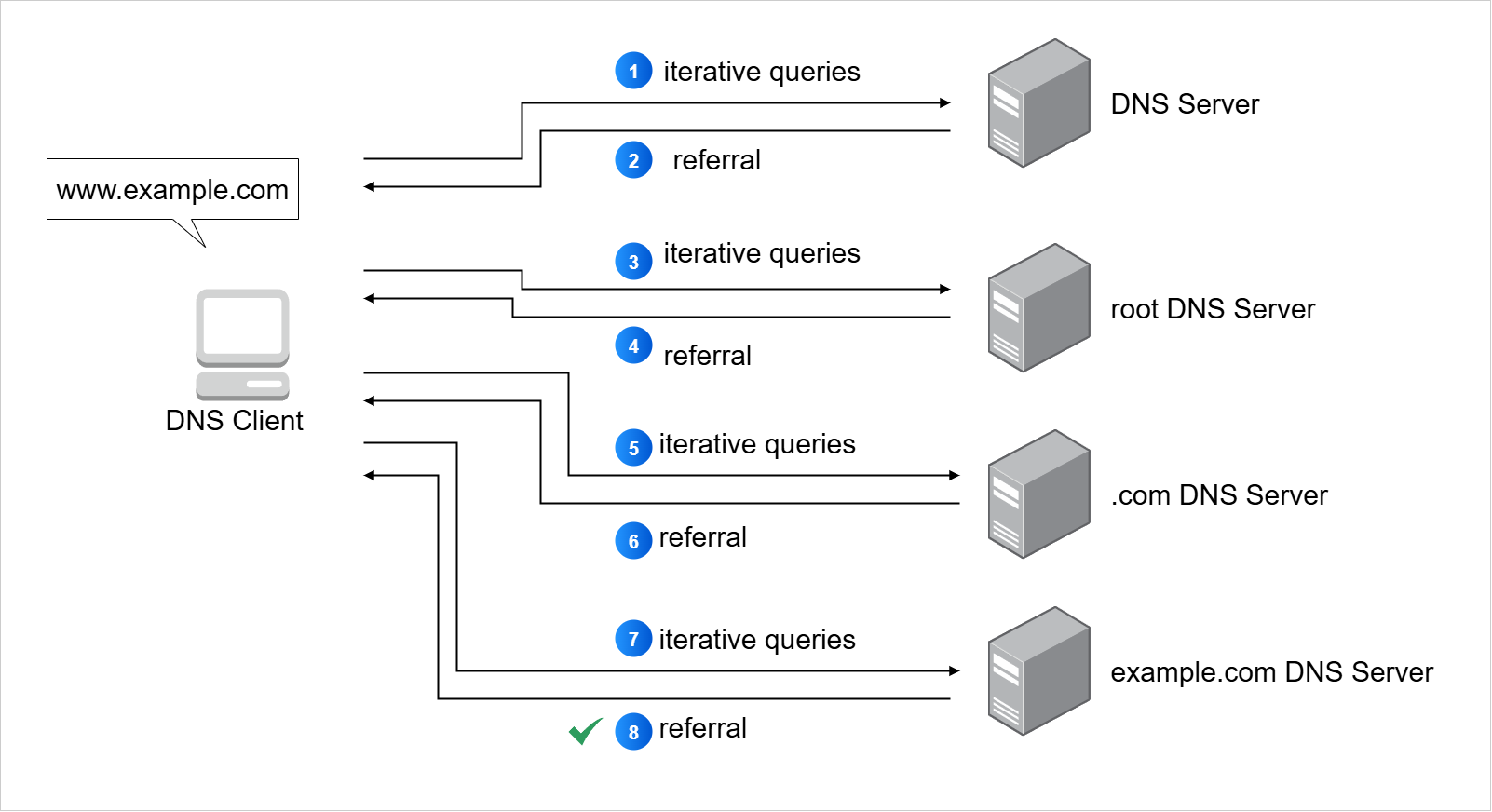

Iterative Resolution

Iterative resolution is a DNS process where the client does most of the work to find an answer.

- Server checks its own data for the answer

- If not found, server sends a referral with other name server addresses

- Client chooses the next server to query

- Process repeats until the authoritative server responds

In this method, each server either gives the answer or points the client to another server. The client keeps sending new queries until it reaches the server that holds the correct information.

This approach works because the client takes responsibility for contacting each server in turn, following the chain until the final answer is found.

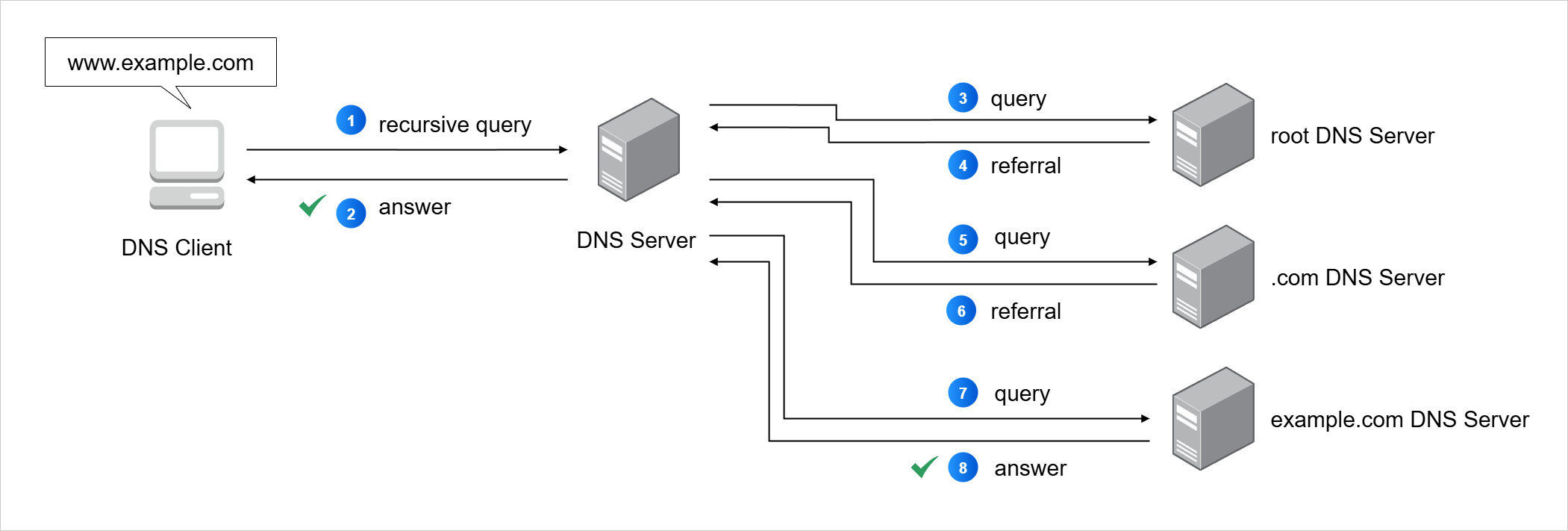

Recursive Resolution

Recursive resolution is a DNS process where the server does all the work to get the answer for the client.

- Client sends a single query to the server

- Server checks its own data first

- If not found, server queries other DNS servers on behalf of the client

- Process continues until the final answer is found and returned

In this method, the client only sends one request. The server then takes over, following the DNS chain from the root down to the authoritative server. The client simply waits for the complete answer without handling referrals.

The key idea is that in recursive resolution, the server is responsible for finding and delivering the requested DNS information.

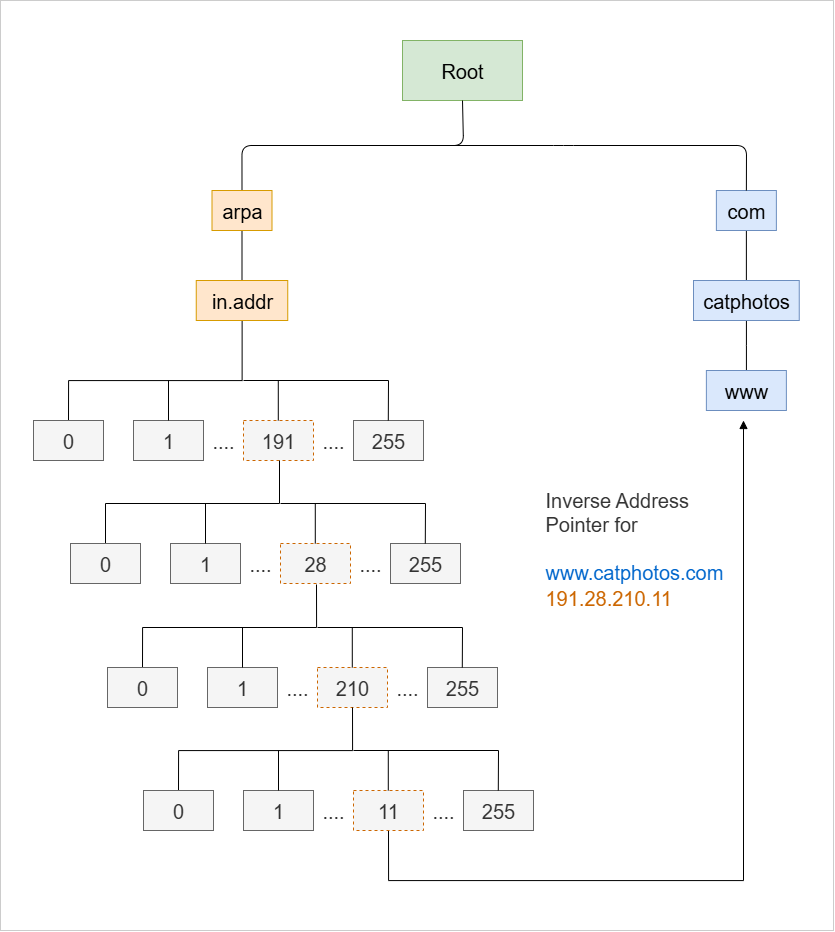

Reverse Name Resolution (rDNS)

Reverse DNS is a system for finding the domain name that belongs to a given IP address. It uses a special domain called in-addr.arpa for IPv4, arranged in a numerical hierarchy.

- Uses a four-level subdomain structure for IPv4 addresses

- Stores each IP address as a reversed set of octets

- Helps in troubleshooting, spam filtering, and logging

The in-addr.arpa hierarchy contains 256 subdomains at each of its four levels, numbered from 0 to 255. Each level corresponds to a section of the IP address, starting from the leftmost octet.

For example:

191.28.210.11

The above IP address is stored as:

11.210.28.191.in-addr.arpa

The IP octets are reversed in the lookup because DNS works from the least specific part to the most specific part, while IP addresses are structured in the opposite way.

-

Example on Linux using

dig:dig -x 191.28.210.11 +noall +answerExpected result:

11.210.28.191.in-addr.arpa. 3600 IN PTR catphotos.com. -

Example on Windows using

ping:ping -a 191.28.210.11Expected result:

Pinging catphotos.com [191.28.210.11] with 32 bytes of data: -

Example on either Windows or Linux using

nslookup:nslookup 69.171.250.35Expected result:

Name: sample-domain.com

Address: 69.171.250.35

Online tools can also perform reverse lookups, such as:

- https://mxtoolbox.com/reverse-lookup.aspx

- https://www.whatismyip.com/reverse-dns-lookup/

- https://www.dnsstuff.com/tools

Reverse lookups are not guaranteed to succeed because they are optional for internet operation. If an organization does not set a reverse DNS record for an IP, the query may return an error.

Example of a missing reverse entry:

nslookup 93.184.216.34

Possible result:

** server can't find 34.216.184.93.in-addr.arpa: NXDOMAIN

Even though reverse DNS is optional, it is useful for for:

- Troubleshooting network issues when only an IP is known

- Filtering spam by verifying sending mail server domains

- Makes logs more readable by replacing IP addresses with domain names

Reverse DNS may not be mandatory, but when in place, it provides useful and human-readable information that makes IP-based work much easier.

Changing Name Resolution Order (Linux)

We can change the order in which a Linux system resolves hostnames by editing the nsswitch.conf file. This file tells the system which sources to check and in what order.

- Controlled by

nsswitch.confin/etc - Affects how hostnames are resolved to IPs

- Sources can include local files, multicast DNS, and regular DNS

The hosts database inside nsswitch.conf determines where the system looks for hostname information. Common sources are:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

files | Refers to /etc/hosts for local mappings |

mdns_minimal | Lightweight multicast DNS for local network name resolution |

dns | Traditional DNS lookups using /etc/resolv.conf |

Checkign the nsswitch.conf file, we can see something like this:

passwd: files

group: files

shadow: files

gshadow: files

hosts: files mdns4_minimal [NOTFOUND=return] dns

networks: files

protocols: db files

services: db files

ethers: db files

rpc: db files

netgroup: nis

The hosts database controls how a Linux system resolved hostnames to IP address and tells the system where to look and in what order.s

hosts: files mdns4_minimal [NOTFOUND=return] dns

This configuration means:

- Check the source

filefirst. - In this case, the source file is the

/etc/hosts - If not found, try multicast DNS (

mdns4_minimal) - If multicast DNS fails with "NOTFOUND," stop the process

- Otherwise, try traditional DNS (

dns)

Example test with /etc/hosts:

# Add this line to /etc/hosts

1.1.1.1 example.com

Test the entry by running ping:

ping example.com

Expected result:

PING example.com (1.1.1.1) 56(84) bytes of data.

Local entries override DNS results even if DNS is listed first in nsswitch.conf. To force DNS to be used, remove or comment out the relevant /etc/hosts entry.

You can query the resolution source using getent:

$ getent hosts example.com

# output below

1.1.1.1 example.com

If the /etc/hosts entry is removed, the system falls back to DNS resolution and the getent will resolve to the public IP address once more:

$ sudo vi /etc/hosts

# Add this line to /etc/hosts

# 1.1.1.1 example.com

$ getent hosts example.com

# output below

2600:1408:ec00:36::1736:7f31 example.com

2600:1406:3a00:21::173e:2e65 example.com

2600:1406:3a00:21::173e:2e66 example.com

2600:1406:bc00:53::b81e:94c8 example.com

2600:1406:bc00:53::b81e:94ce example.com

2600:1408:ec00:36::1736:7f24 example.com

Best Practices

Key points when modifying nsswitch.conf:

- Always back up the file before making changes

- Keep

filesas the first source unless there's a strong reason not to - Avoid overly complex rules;

files dnsis enough for most setups - Use optional actions like

[NOTFOUND=return]with care, as they can stop lookups early

By adjusting nsswitch.conf and understanding the precedence of /etc/hosts, you can control exactly how and where your system resolves hostnames.