Classes: Inheritance

Overview

Inheritance allows one class to reuse methods from another class. It helps reduce duplicated code and makes it easier to model related ideas in a clear hierarchy.

In Ruby, inheritance works with two main roles:

- A parent class (also called a superclass or base class) provides methods

- A child class (also called a subclass) receives them.

A class can inherit from only one parent, but inheritance can extend through multiple levels, with general behavior passed down to more specific classes.

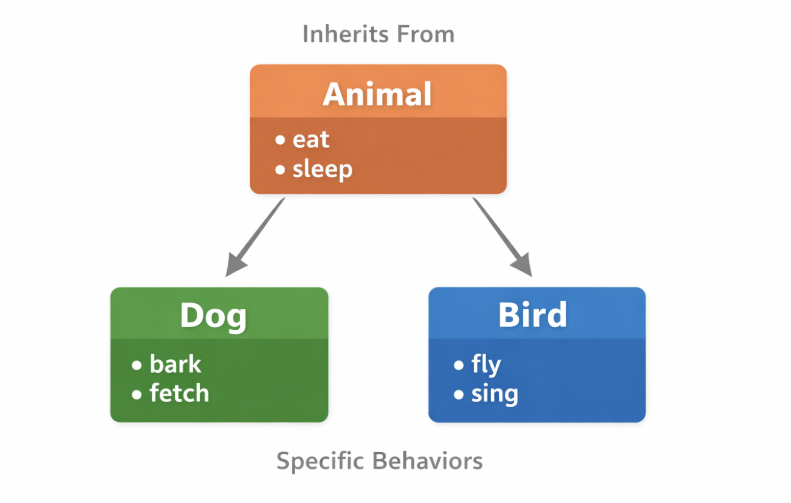

For example, if you model animals, an Animal class can define shared behavior like eating or sleeping, while Dog or Bird classes can add their own specific actions. This keeps common logic in one place and makes the code easier to extend and maintain.

Declaring Subclasses

A subclass gets all the functionality of its parent class and can also add its own unique methods.

To create a subclass, write the subclass name followed by < and the superclass it inherits from. For example, writing Dog < Animal makes Dog inherit from the Animal class.

class Animal

attr_reader :type, :action

def initialize(type, action)

@type = type

@action = action

end

def perform

"The #{@type} can #{@action}"

end

end

# Subclass "Dog" inheriting from "Animal"

class Dog < Animal

end

# Subclass "Bird" inheriting from "Animal"

class Bird < Animal

end

# Creating objects

fido = Dog.new("dog", "bark and fetch")

tweety = Bird.new("bird", "fly and sing")

puts fido.perform

puts tweety.perform

Output:

The dog can bark and fetch

The bird can fly and sing

Even though Dog and Bird have no methods defined inside them, they automatically get the initializer, readers, and instance methods from Animal. This avoids repeating code and allows each subclass to be extended with its own behavior later.

superclass and ancestors

Every class can inherit from another class, which forms a hierarchy. The superclass and ancestors methods help you see where a class gets its methods.

superclassshows the immediate parent classancestorslists all classes and modules that provide behavior

Consider the Animal hierarchy below. We can see that the Dog inherits from Mammal, which inherits from Animal, and so on.

class Animal

end

class Mammal < Animal

end

class Dog < Mammal

end

puts Dog.superclass

puts Mammal.superclass

puts Animal.superclass

puts Object.superclass

puts BasicObject.superclass

Output:

Mammal

Animal

Object

BasicObject

The Object class inherits from BasicObject, which is the top-level class in Ruby and does not have a superclass, so calling BasicObject.superclass returns nil or none.

The ancestors method shows the full chain of inheritance for a class, including all the classes and modules. For example:

puts Dog.ancestors.inspect

Output:

[Dog, Mammal, Animal, Object, Kernel, BasicObject]

When the ancestors method is called, it shows the full inheritance chain of a class, including any mixins that have been added to the class or its superclasses.

For more information, please see Mixins.

The classes can also be written in a compact form:

class Animal; end

class Mammal < Animal; end

class Dog < Mammal; end

puts Dog.superclass

puts Mammal.superclass

puts Animal.superclass

puts Object.superclass

puts BasicObject.superclass

Chaining superclass

You can trace a class's inheritance chain by chaining the superclass method. This shows each parent class in the hierarchy. Once you reach BasicObject, calling superclass returns nil, which basically means you've reached the end of the hierarchy.

class Animal

end

class Mammal < Animal

end

class Dog < Mammal

end

puts Dog.superclass # Output: Mammal

puts Dog.superclass.superclass # Output: Animal

puts Dog.superclass.superclass.superclass # Output: Object

puts Dog.superclass.superclass.superclass.superclass # Output: BasicObject

puts Dog.superclass.superclass.superclass.superclass.superclass # Output: nil

Another good example is chaining superclass on an integer like 27. Since 27 is an object, not a class, we first call class to get its class, and then chain superclass to see the inheritance hierarchy:

puts 27.class # Output: Integer

puts 27.class.superclass # Output: Numeric

puts 27.class.superclass.superclass # Output: Object

puts 27.class.superclass.superclass.superclass # Output: BasicObject

puts 27.class.superclass.superclass.superclass.superclass # Output: nil

instance_of? and is_a?

You can find out what class an object belongs to and whether it inherits from another class using the instance_of? and is_a? methods. These are instance methods, so you call them on the object itself, not on the class

instance_of?returnstrueif object was created from the class you passis_a?returnstrueif the object is from that class or any class it inherits from.

For example, consider a simple animal hierarchy:

class Animal; end

class Mammal < Animal; end

class Dog < Mammal; end

fido = Dog.new

The instance_of? checks if the object is exactly an instance of the given class:

puts fido.instance_of? Dog # Output: true

puts fido.instance_of? Mammal # Output: false

puts fido.instance_of? Animal # Output: false

The is_a? checks if the object is an instance of the given class or any of its superclasses:

puts fido.is_a? Dog # true

puts fido.is_a? Mammal # true

puts fido.is_a? Animal # true

puts fido.is_a? Object # true

methods Method

Every object in Ruby has a methods instance method. This returns an array of all the methods available to that object, including those inherited from superclasses. You can also sort this array to view the methods neatly.

Examples:

-

You can call

methodson an integer object and then runsort:num = 5

integer_methods = num.methods.sort

p integer_methodsOutput:

[:!, :!=, :!~, :%, :*, :**, :+, :+@, :-, :-@, :/, :<, :<=, :<=>, :==, :===, :>, :>=, :Namespace,

:TypeName, :__id__, :__send__, :abs, :abs2, :angle, :arg, :between?, :ceil, :clamp, :class, :clone,

:coerce, :conj, :conjugate, :define_singleton_method, :denominator, :display, :div, :divmod, :dup,

(output truncated) -

For a float object:

flt = 3.5

float_methods = flt.methods.sort

p float_methodsOutput:

[:!, :!=, :!~, :%, :*, :**, :+, :+@, :-, :-@, :/, :<, :<=, :<=>, :==, :===, :>, :>=, :Namespace,

:TypeName, :__id__, :__send__, :abs, :abs2, :angle, :arg, :between?, :ceil, :clamp, :class, :clone,

:coerce, :conj, :conjugate, :define_singleton_method, :denominator, :display, :div, :divmod, :dup,

(output truncated) -

You can compare objects to see which methods they share or which are unique.

For example, to find common methods between an integer and a float:

num = 5

integer_methods = num.methods

flt = 3.5

float_methods = flt.methods

common_methods = integer_methods & float_methods

p common_methodsOutput:

[:abs, :floor, :ceil, :round, :truncate, :-@, :**, :<=>, :>=, :==, :===, :<=,

:zero?, :%, :integer?, :*, :+, :numerator, :-, :rationalize, :inspect, :/, :denominator,

:<, :>, :to_int, :to_s, :to_i, :to_f, :to_r, :div, :divmod, :fdiv, :coerce, :modulo,

(output truncated) -

To find methods unique to a float:

unique_float = 3.5.methods - 3.methods

p unique_float -

To find methods unique to an integer:

unique_integer = 3.methods - 3.5.methods

p unique_integer

Exclusive Methods in Subclasses

A subclass can add its own methods while still keeping everything from its superclass. This lets each subclass be a more specific version of the parent class.

Consider a simple Animal superclass with two subclasses: Dog and Bird. Both share the common behavior from Animal class, but each has its own behavior that only makes sense for that type.

class Animal

attr_reader :type, :action

def initialize(type, action)

@type = type

@action = action

end

def perform

"The #{@type} can #{@action}"

end

end

class Dog < Animal

def bark

"Woof"

end

end

class Bird < Animal

def fly

"Tweet tweet"

end

end

Using these classes:

buddy = Dog.new("Dog", "run and fetch")

tweety = Bird.new("Bird", "fly and sing")

p buddy.bark

p tweety.fly

p buddy.perform

p tweety.perform

Output:

"Woof"

"Tweet tweet"

"The Dog can run and fetch"

"The Bird can fly and sing"

Same method name, different behavior

Different subclasses can also define the same method name but implement it differently.

class Dog < Animal

def action

"Run until I get tired"

end

end

class Bird < Animal

def action

"Fly until it rains"

end

end

Calling the same method on different objects:

p buddy.action

p tweety.action

Output:

"Run until I get tired"

"Fly until it rains"

Even though the method name is the same for both subclasses, each subclass defines its own action, so the behavior depends on the object’s class.

Override Methods in a Subclass

Method overriding happens when a subclass defines a method with the same name as one in its superclass. Ruby will use the subclass version first, and the superclass version is only used if the subclass doesn’t define it.

To see this clearly, consider a simple Animal hierarchy.

class Animal

def speak

"The animal makes a sound"

end

end

class Dog < Animal

def speak

"The dog barks"

end

end

class Bird < Animal

end

Now create objects and call the same method on each one.

dog = Dog.new

bird = Bird.new

puts dog.speak

puts bird.speak

Output:

The dog barks

The animal makes a sound

Even though the speak method exists in Animal, the Dog version is used because it overrides the method in the superclass. Since Bird does not define its own speak method, Ruby moves up the inheritance chain and uses the one from Animal.

This happens because Ruby always looks for a method starting from the object’s class, then checks its parent classes one by one until it finds a match.

Using the super keyword

The super keyword lets a subclass run the same method from its superclass, so you can reuse existing behavior and add extra functionality.

superpasses all arguments to the superclasssuper()passes no argumentssuper(args)passes only the given arguments

Example 1: Simple Subclass

This example shows how a Dog subclass can reuse and extend the behavior of its parent Animal class using the three forms of super.

class Animal

attr_reader :name

def initialize(name)

@name = name

end

# Parent's `action`

def action(activity)

"#{@name} is #{activity}"

end

# Parent's `greet`

def greet

"Hi, I'm #{@name}"

end

end

class Dog < Animal

attr_reader :breed

# 1. Using `super(arg)`

def initialize(name, breed)

super(name)

@breed = breed

end

# 2. Using `super`

def action(activity)

super + " happily in the park"

end

# 3. Using `super()`

def greet

super() + " and I'm a dog"

end

end

dog = Dog.new("Buddy", "Beagle")

puts dog.name

puts dog.greet

puts dog.action("running")

Output:

Buddy

Hi, I'm Buddy and I'm a dog

Buddy is running happily in the park

Explanation:

super(name)ininitializereuses parent setup so subclass only handlesbreed.superin action reuses the parent behavior and adds extra text. -super()ingreetcalls parent method without arguments, then adds its own text.

Example 2: Practical Project Scenario

This example shows a project-like scenario where the Bug subclass extends the Task class.

class Task

attr_reader :title, :priority

def initialize(title, priority)

@title = title

@priority = priority

end

# Base status message

def status

"#{@title} is in progress"

end

# Base description

def description

"Task: #{@title}, Priority: #{@priority}"

end

end

class Bug < Task

attr_reader :severity

# 1. Using `super(arg)`

def initialize(title, priority, severity)

super(title, priority)

@severity = severity

end

# 2. Using `super` (no parentheses) to extend status

def status

super + " and needs attention"

end

# 3. Using `super()` (no arguments) to extend description

def description

super() + ", Severity: #{@severity}"

end

end

# Create a bug instance

bug = Bug.new("Login error", "High", "Critical")

puts bug.title

puts bug.priority

puts bug.severity

puts bug.status

puts bug.description

Output:

Login error

High

Critical

Login error is in progress and needs attention

Task: Login error, Priority: High, Severity: Critical

Explanation:

super(title, priority)reuses the parentinitializelogic.superin status extends the parent output with extra information.super()in description calls the parent method without arguments, then adds subclass-specific details.

Defining Equality for Objects

By default, Ruby only considers objects equal if they are the exact same instance. You can override this behavior by defining your own logic for equality.

In the Book class below, we define equality using the == method to compare pages and price.

Both book1 and book2 are considered equal because they have the same pages and price, while book1 and book3 is are not equal because one or both attributes differ.

class Book

attr_reader :title, :pages, :price

def initialize(title:, pages:, price:)

@title = title

@pages = pages

@price = price

end

def ==(other)

pages == other.pages && price == other.price

end

end

book1 = Book.new(title: "Ruby Basics", pages: 200, price: 25)

book2 = Book.new(title: "Advanced Ruby", pages: 200, price: 25)

book3 = Book.new(title: "Learning Rails", pages: 150, price: 20)

puts book1 == book2

puts book1 == book3

Output:

true

false

Duck Typing

Duck typing is about focusing on what an object can do rather than what class it comes from. Any object that supports the methods you need can be used interchangeably with others that have the same methods.

Duck typing actually comes from the saying:

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck.

In programming, this means an object doesn’t need to be a specific clas, it just needs the right behavior.

For example, we have a Drink class that defines equality based on volume and price. We can compare a Drink object with a Juice object, even though they are different classes, as long as both have volume and price methods:

class Drink

attr_reader :name, :volume, :price

def initialize(name:, volume:, price:)

@name = name

@volume = volume

@price = price

end

def ==(other)

volume == other.volume && price == other.price

end

end

class Juice

attr_reader :volume, :price

def initialize(volume:, price:)

@volume = volume

@price = price

end

end

drink1 = Drink.new(name: "Cola", volume: 500, price: 2)

juice1 = Juice.new(volume: 500, price: 2)

juice2 = Juice.new(volume: 300, price: 1)

puts drink1 == juice1

puts drink1 == juice2

Output:

true

false

Here, drink1 == juice1 is true because both objects have the same volume and price. The class doesn’t matter, only the methods do.