Regular Expressions

Regex

A regular expression (regex) is a an object used to search text using patterns. It is more flexible than simple string methods and it can match complex sequences of characters.

To start with, we can use simple string methods like include?, start_with?, and end_with? for basic checks without needing regex. For example:

quote = "Violence is the last refuge of the incompetent"

puts quote.include?("ref")

# Output: true

puts quote.start_with?("Violen")

# Output: true

puts quote.end_with?("mpetent")

# Output: true

These methods work for simple checks, but regex can handle more complex searches.

To create a regex object, use two forward slashes (//) with the pattern inside. For example, to look for the letter "V":

pattern = /V/

You can search a string using the =~ operator:

puts quote =~ /V/

# Output: 0, because the letter "V" is in index 0.

puts quote =~ /e/

# Output: 4

You can also put the regex on the left side:

puts /s/ =~ quote

# Output: 10

Because quote holds the string, Ruby scans each character and returns the index of the first match. For example, the first "s" appears in "is," so it returns that position.

If the pattern is not found, Ruby returns nil. Regex matches sequences exactly as written, including letters, symbols, or multiple characters:

puts quote =~ /Be?/

# Output: nil

puts quote =~ /alive!/

# Output: nil

Using scan

The scan method finds all matches of a regex pattern in a string and returns them in an array. This is useful when you want every match, not just the first one.

For example, create a string representing a quote:

quote = "Logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end."

You can find all "e" letters like this:

quote.scan(/e/)

# Output: ["e", "e", "e", "e"]

You can also search for consecutive characters:

quote.scan(/is/)

# Output: ["is", "is"]

To match any character from a set, use square brackets:

quote.scan(/[th]/)

# Output: ["t", "h", "t", "t", "h"]

The method scans the string from start to end, collects matches, and returns them in order.

Matching Digits

The \d symbol in regex matches any digit from 0 to 9. You can combine it with other symbols to find sequences of digits, which is useful for extracting numbers from text like phone numbers or IDs.

\dmatches any single digit+finds one or more consecutive digits{n}matches exactly n digits{n,}matches at least n digits{n,m}matches between n and m digits

For example, using a voicemail string:

message = "Order ID: AB-2023-98765, contact support if needed"

message.scan(/\d/)

# Output: ["2","0","2","4","9","8","7","6","5"]

message.scan(/\d+/)

# Output: ["2023", "98765"]

message.scan(/\d{4}/)

# Output: ["2023"]

message.scan(/\d{3,}/)

# Output: ["2023", "98765"]

message.scan(/\d{2,4}/)

# Output: ["2023", "9876"]

Using the Dot (.) Wildcard

The dot (.) is a wildcard that matches any single character, which makes it useful when parts of a string can change.

On its own, the dot is very broad. If you scan a string with just ., Ruby will match every character.

Basic wildcard matching:

text = "Please call support at 777 888 9999 or email helpdesk@sample.org"

text.scan(/.a/)

# Output: ["ea", " ca", " at", " sa", "amp"]

This pattern means “any character followed by a”. Ruby scans the string and returns each matching pair. You do not need to know what comes before a, which makes the match flexible.

If you add another wildcard, the match expands:

text.scan(/.a./)

# Output: ["eas", " cal", " at ", " sam", "amp"]

Here, the a is matched with any character before and after it.

1. Extracting phone numbers with changing separators

Sometimes phone numbers are written with dashes, spaces, or other symbols. We can use the dot to handle the differences:

text = "Please call support at 777 888 9999 or email helpdesk@sample.org"

text.scan(/\d{3}.\d{3}.\d{4}/)

# Output: ["777 888 9999"]

This pattern means:

- Three digits

- Any single character

- Three digits

- Any single character

- Four digits

It works even if the separator changes, because the dot accepts any character in between.

If the number of separators is inconsistent, you can allow one or more wildcards:

text = "Please call support at 777--888 9999"

text.scan(/\d{3}.+\d{3}.+\d{4}/)

# Output: ["777--888 9999"]

The .+ means one or more of any character. Ruby keeps scanning until it finds the next digit group, which makes the pattern resilient to spacing or symbol changes.

2. Matching a literal dot

The dot normally means “any character”, so it cannot match a real period by itself. To match an actual dot, you must escape it.

email = "helpdesk@sample.org"

email.scan(/\./)

# Output: ["."]

Escaping tells Ruby to treat the dot as a literal character. This is important when parsing emails or domains, where the period itself matters.

Matching the Start and End of Strings

Anchors let you match a pattern only at a specific position in a string. They do not match characters themselves, but instead point to a location.

- Anchors can target the start of a string

- Anchors can target the end of a string

- They help avoid matching the same pattern in the middle

This is useful when the same text appears multiple times but only one position actually matters.

Start Anchor

The \A anchor tells Ruby to start matching from the very beginning of the string.

message = "404 error occurred. Please try again. Error code 404"

message.scan(/\A\d+/)

# Output: ["404"]

Here, \d+ means one or more digits, and \A forces Ruby to only look at the start. Even though 404 appears again later, only the first one is returned. This keeps the match focused on the beginning, which is the key idea of a start anchor.

If the string does not begin with digits, nothing is returned:

message = " Error 404 occurred"

message.scan(/\A\d+/)

# Output: []

End Anchor

The \z anchor tells Ruby to match only at the very end of the string.

log = "Backup completed successfully..."

log.scan(/\.\z/)

# Output: ["."]

This pattern looks for a literal dot right before the end of the string. Even if there are other dots earlier, only the last one is matched because of the end anchor.

You can also match multiple characters at the end:

log.scan(/\.+\z/)

# Output: ["..."]

The + allows one or more dots, but \z ensures they must be at the end. Any dots in the middle are ignored, which brings the focus back to matching by position instead of content.

Excluding Characters

You can tell regex to match characters you do not want. This is useful when you want the opposite of a normal character match.

Consider the sample string below:

text = "You've ordered: 7 fruits, 15 bread, 9 milk, and 12 eggs"

If you want to match specific characters, you normally list them inside square brackets.

text.scan(/[aeiou]/)

# Output: ["o", "u", "e", "o", "e", "e", "u", "i", "e", "a", "i", "a", "e"]

The square brackets matches any lowercase vowel. It basically means “match one of these characters".

Using caret (^)

To exclude characters, place a caret (^) at the start of the brackets.

p text.scan(/[^aeiou]/)

Output:

["Y", "'", "v", " ", "r", "d", "r", "d", ":", " ", "7", " ", "f", "r", "t", "s", ",", " ", "1", "5", " ", "b", "r", "d", ",", " ", "9", " ", "m", "l", "k", ",", " ", "n", "d", " ", "1", "2", " ", "g", "g", "s"]

This means “match any character that is not a, e, i, o, or u.” The result includes consonants, spaces, digits, and punctuation. The caret flips the meaning of the character list, which is the core idea behind exclusion.

Narrowing down

To keep only consonants, you must exclude everything else.

p text.scan(/[^aeiouAEIOU\d\s\.,:]/)

# Output: ["Y", "'", "v", "r", "d", "r", "d", "f", "r", "t", "s", "b", "r", "d", "m", "l", "k", "n", "d", "g", "g", "s"]

Here is what is excluded:

- Vowels in lowercase and uppercase

- Digits using

\d - Spaces using

\s - Common punctuation like dots, commas, and colons

By excluding these, only consonant letters remain. This shows how exclusion helps you filter a string by defining what should be left out rather than what should be kept.

Using sub and gsub

The sub and gsub methods replace parts of a string, and works like a simple find-and-replace method.

subreplaces only the first matchgsubreplaces all matches- Both return a new string by default

Consider the sample string below:

code = "AB 123 CD 456"

Using sub replaces only the first space:

code.sub(" ", "-")

# Output: "AB-123 CD 456"

Using gsub replaces all spaces in one step:

code.gsub(" ", "-")

# Output: "AB-123-CD-456"

Replace Multiple Characters

Let's use the example string below:

reference = "ID-(789)-456-1234"

If you try to remove several characters without regex, you must chain calls.

cleaned = (

reference

.gsub("-", "")

.gsub("(", "")

.gsub(")", "")

)

puts cleaned

# Output: "ID7894561234"

This works, but it is repetitive and harder to maintain. The idea is correct, but the approach can be simplified. A much easier way is to use gsub with regex to target many characters at once.

reference = "ID-(789)-456-1234"

cleaned = reference.gsub(/[-()]/, "")

puts cleaned

# Output: "ID7894561234"

The square brackets mean “match any one of these characters.” Every match is replaced with an empty string, which removes it.

Modify the Original String

By default, sub and gsub do not change the original string. If you want to update it directly, use the bang (!) versions.

reference.gsub!(/[-()]/, "")

puts reference

# Output: "ID7894561234"

This overwrites the original value, which is useful when you intentionally want to mutate the string.

Practice Regex with Rubular

You can practice regex using sites like Rubular.com:

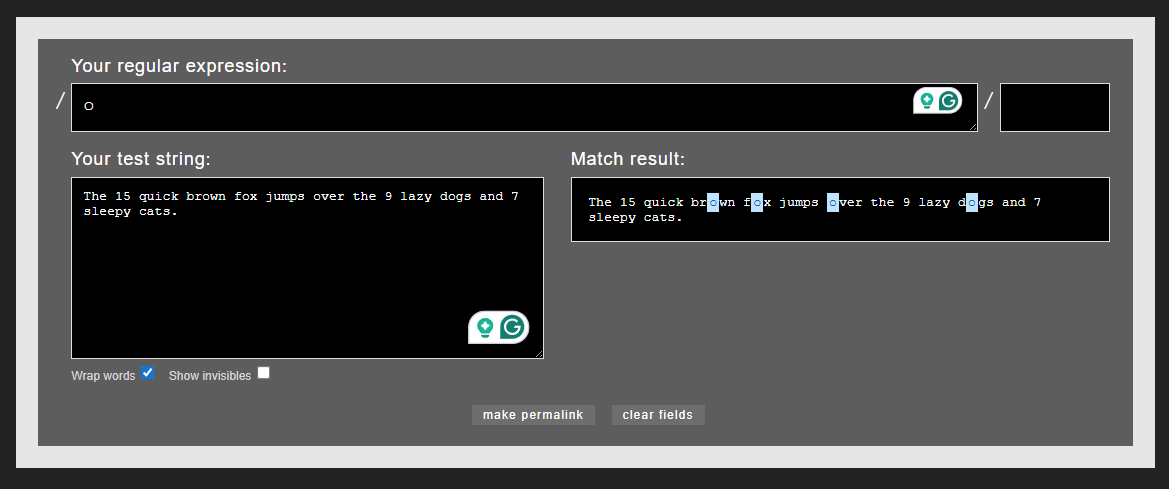

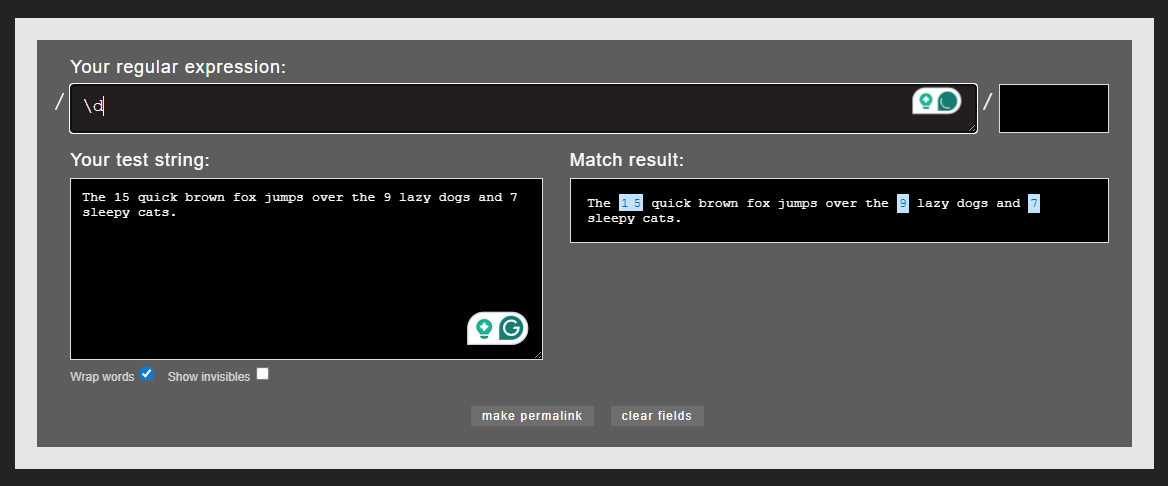

Use this string as example:

The 15 quick brown fox jumps over the 9 lazy dogs and 7 sleepy cats.

If you use the letter o as a pattern, it highlights all occurrences of o:

To search for digits, use \d, which highlights all numbers in the string:

You can use this to experiment, test different patterns, and then copy the working regex into your code.