Exceptions

Overview

Exceptions happen when Ruby cannot run a piece of code correctly. This can be a syntax mistake or a logical problem like adding a number to text.

Using begin and rescue

We can use begin and rescue to catch these errors and handle them instead of letting the program crash.

beginmarks a block of code that might failrescuedefines how to handle any error in the begin block

For example, a simple method to sum two values:

# sum.rb

def sum(a, b)

a + b

end

puts sum(3, "5")

If we run the code, it will return an error because Ruby cannot add an integer (3) and a string ("5"):

ruby sum.rb

Output:

'Integer#+': String can't be coerced into Integer (TypeError)

We can fix this by wrapping the potentially failing code in a begin block. This tells Ruby to be mindful that an error might occur. Then we add a rescue block to handle the error safely:

def sum(a, b)

begin

a + b

rescue

"Unknown"

end

end

puts sum(3,5) # Output: 8 (No error)

puts sum(3, "5") # Output: Unknown (Type error happens)

puts sum(nil, nil) # Output: Unknown (NoMethod error happens)

The rescue block runs only if an exception occurs, and code outside the begin/rescue continues normally. This keeps the program running even when unexpected errors happen.

Capturing Specific Errors

You can make rescue more precise by capturing specific error types and accessing their details. This lets you handle different errors differently instead of using a catch-all.

In this example, each error has its own rescue block:

def sum(a, b)

begin

a + b

rescue TypeError => error

puts "Type error: #{error.class} - #{error.message}"

rescue NoMethodError => error

puts "No method error: #{error.class} - #{error.message}"

end

end

puts sum(2, 7)

puts sum(3, "5")

puts sum(nil, nil)

Output:

9

Type error: TypeError - String can't be coerced into Integer

No method error: NoMethodError - undefined method '+' for nil

By naming the error object, you can check its class and message and decide how to respond.

Using retry

You can use retry in a rescue block to fix an error and run the code again. This sends Ruby back to the begin block and lets the program recover from errors automatically.

Note: Make sure to adjust or correct the problem before retrying, otherwise it can create an infinite loop.

For example, we can update the sum method to handle invalid inputs and retry:

def sum(a, b)

begin

a + b

rescue TypeError

a = a.to_i

b = b.to_i

retry

rescue NoMethodError

a = 0

b = 0

retry

end

end

puts sum(7, 9)

puts sum(6, "11")

puts sum(nil, nil)

Output:

16

17

0

Using ensure

The ensure keyword runs a section of code no matter what happens in a begin or rescue block. It is mostly used for cleanup, like closing files or database connections.

For example, if you open a file or connect to a database, ensure makes sure you close it even if an error occurs.

In the code below, we try to read a file and print its contents. If the file doesn’t exist, it is created. Finally, the ensure block makes sure the file is always closed.

# read_file.rb

def read_file(file_name)

begin

file = File.open(file_name, "r")

content = file.read

puts "file content: #{content}"

rescue Errno::ENOENT

puts "file not found, creating a new one"

File.write(file_name, "new content")

retry

ensure

file.close if file

puts "file closed"

end

end

read_file("hello.txt")

Running the script:

ruby read_file.rb

Output if file exists:

file content: Hello world!

file closed

Modify the code and change the text file name (for example, change to hello1.txt). Then re-reun the code.

# read_file.rb

def read_file(file_name)

....

end

read_file("hello1.txt")

Since the file doesn't exist, it will create the file:

file not found, creating a new one

file content: new content

file closed

ensure always runs, whether the code succeeds or an error occurs. It guarantees cleanup or mandatory actions happen at the end of your block.

Two ways to use begin and rescue

We can handle exceptions in two main ways:

- Inside a method

- At the top level of a program.

Both use the same begin, rescue, and ensure keywords, but the syntax and flexibility differ slightly.

1. Within a Method

Inside a method, the begin keyword is optional. Ruby automatically treats the method body as a block where exceptions can occur. You can simply write your code and follow it with rescue and ensure.

def divide(a, b)

result = a / b

puts "Result is #{result}"

rescue ZeroDivisionError

puts "Cannot divide by zero"

ensure

puts "Method complete"

end

divide(15, 3)

divide(11, 0)

Output:

Result is 5

Method complete

Cannot divide by zero

Method complete

Here, rescue catches errors that happen in the method, and ensure always runs, whether an error occurs or not. This keeps exception handling close to the code that might fail.

2. At the Top Level

You can also use begin and rescue outside any method, at the top level of the Ruby file. This allows you to handle errors in code that runs as the main program.

# open_file.rb

begin

puts "opening file"

content = File.read("my-grocery-list.txt")

rescue Errno::ENOENT

puts "File not found"

ensure

puts "Program finished"

end

Output if file is missing:

Opening file

Program finished

If we change the file name to my-shopping-list.txt and re-run the code:

# open_file.rb

begin

puts "Opening file"

content = File.read("my-shopping-list.txt")

...

Output:

Opening file

File not found

Program finished

At the top level, you cannot manipulate method parameters like a or b because no method scope exists. ensure still runs, and you can also use retry carefully to rerun the begin block if needed.

Using raise

The raise keyword is used to manually trigger an error in your program. It is used to protect your program logic and tells Ruby that a situation is invalid, and it should stop execution.

In the code below, we model a simple bank account. A withdrawal is only allowed if there is enough balance. If not, we manually raise an error.

class BankAccount

attr_accessor :balance

def initialize

@balance = 0

end

def deposit(amount)

@balance += amount

end

def withdraw(amount)

raise "Insufficient balance" if amount > balance

@balance -= amount

puts "Withdrew #{amount}"

end

end

account = BankAccount.new

puts account.deposit(100) # Output: Withdrew 30

puts account.withdraw(30) # Output: Insufficient balance (RuntimeError)

puts account.withdraw(200) # Output: Insufficient balance (RuntimeError)

Here, Ruby has no technical problem running the code, but withdrawing more money than available does not make sense. By using raise, we clearly tell Ruby to stop and treat this situation as an error.

Custom Exception Hierarchy

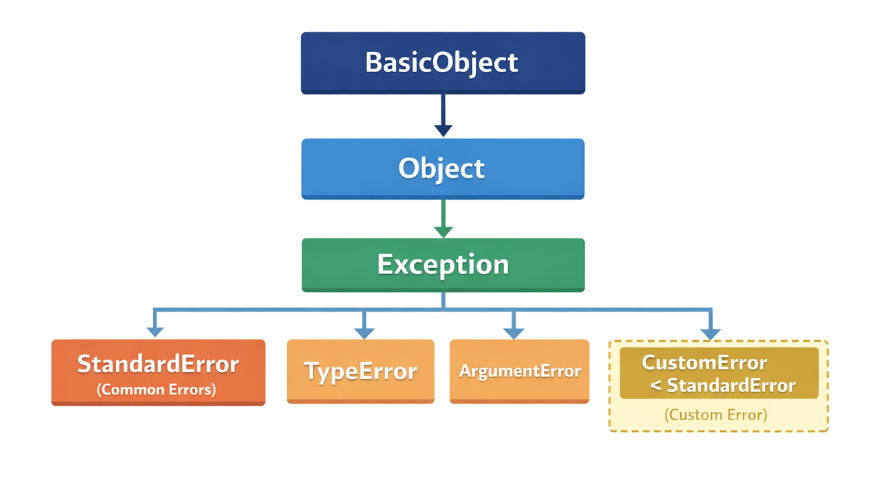

Ruby errors are objects that follow an inheritance hierarchy. This allows us to define our own error classes and handle real-world rules clearly.

At the top, everything inherits from BasicObject, then Object, then Exception. Under Exception are more specific errors like:

StandardErrorTypeErrorArgumentError

Most Ruby errors we see are subclasses of StandardError, which is why custom errors should also inherit from it. This keeps them compatible with rescue.

Raising a Custom Error

Sometimes Ruby cannot detect a logical problem by itself. In those cases, we can define a custom error to represent a real-world rule and raise it intentionally.

In the code below, we model a simple door system. A door must be unlocked before it can be opened. If it is locked, we raise a custom error.

class DoorLockedError < StandardError

end

class Door

attr_accessor :locked

def initialize

@locked = true

end

def unlock

@locked = false

end

def open

raise DoorLockedError, "Door is locked" if locked

puts "Door opened"

end

end

This custom error clearly explains what went wrong. Ruby does not know that a locked door cannot be opened, so we use raise to enforce that rule and keep the logic correct.

Rescuing a Custom Error

Custom errors can be rescued just like built-in Ruby errors. This lets us react differently based on the exact problem.

In the code below, we catch the custom error, fix the issue, and retry the operation.

door = Door.new

begin

door.open

rescue DoorLockedError => e

puts e.message

puts "Unlocking door and trying again"

door.unlock

retry

end

Output:

Door is locked

unlocking door and trying again

Door opened

Explanation of the code structure: The full code can be seen below. Notice that the logic for "Door is locked" if locked is inside the Door class and not in DoorLockedError class. The main reason for is responsibility separation.

- The

Doorclass is responsible for behavior and state. - The

DoorLockedErrorclass is only responsible for describing an error, not deciding when it happens.

Only the Door class knows:

- Whether it is locked

- What “opening” means

- When opening is allowed

So the decision must live in the Door class.

class DoorLockedError < StandardError

end

class Door

attr_accessor :locked

def initialize

@locked = true

end

def unlock

@locked = false

end

def open

raise DoorLockedError, "Door is locked" if locked

puts "Door opened"

end

end

door = Door.new

begin

door.open

rescue DoorLockedError => e

puts e.message

puts "Unlocking door and trying again"

door.unlock

retry

end