Choosing Encryption Algorithms

Overview

Encryption algorithms vary in strength and purpose. Choosing the right one depends on how well it supports the four goals of cryptography:

- Confidentiality

- Integrity

- Authentication

- Non-repudiation

For strong protection, rely on algorithms tested and reviewed by the security community to ensure they are safe, reliable, and free of backdoors.

Work function is the amount of time and computing power needed to break a cryptographic system. It measures how resistant an algorithm is to attacks based on current technology.

The size of the work function should be matched against the relative value of the protected asset.

Key Considerations

-

Proven Algorithms

- Choose algorithms with extensive public evaluation.

- Ensure acceptance in the security community.

-

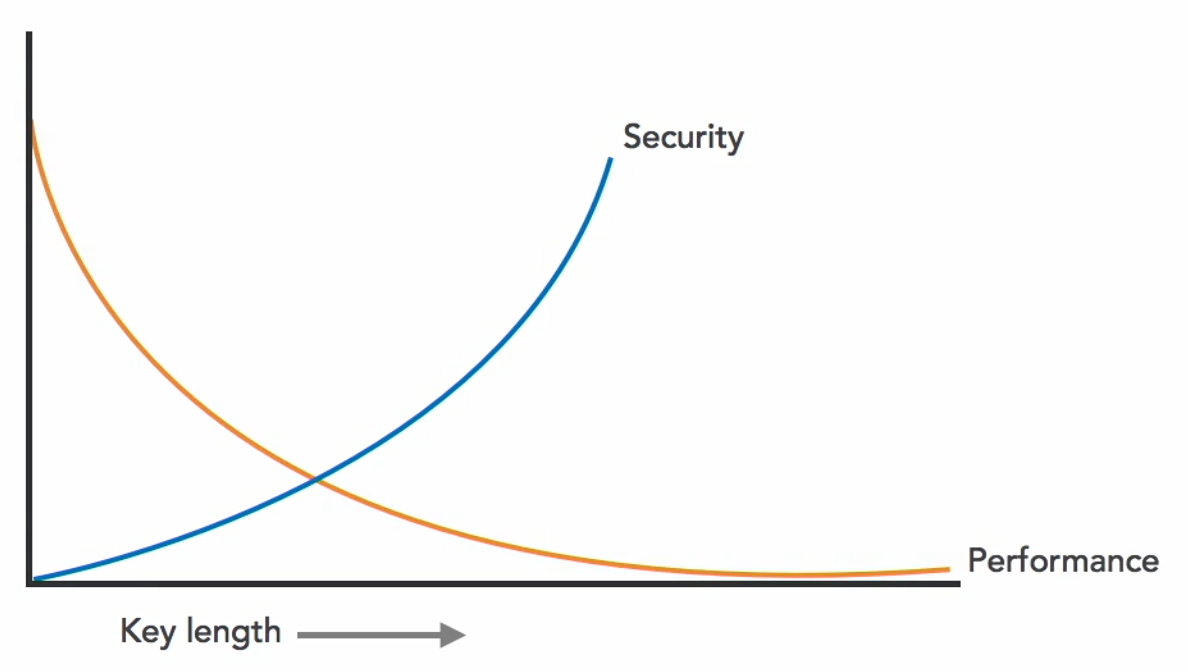

Key Length

- Longer keys are more secure by making them harder to guess.

- Longer keys can reduce performance.

- Balance security with system speed.

-

Vulnerability to Brute Force

- Longer keys increase possible combinations.

- Makes them more resistant to brute-force attacks.

Key Length

Key length is a major factor in encryption strength. Longer keys are harder to break but can slow performance, so there is always a trade-off.

- 40-bit keys once seemed strong but are easily broken today

- 128-bit keys provide solid security for most uses

- 1024-bit (and beyond) offers stronger protection but with more processing cost

Ultimately, selecting an encryption method involves balancing security needs with performance requirements through careful analysis of key length and algorithm choice.

One-Time Pad: A Perfect Cipher

The one-time pad is the only cipher proven to be unbreakable. It is invented over a century ago, and it relies on true randomness and identical pads shared between sender and receiver.

:::

The one-time pad was invented by Gilbert Vernam in 1917, thus sometimes referred to as the Vernam cipher.

:::

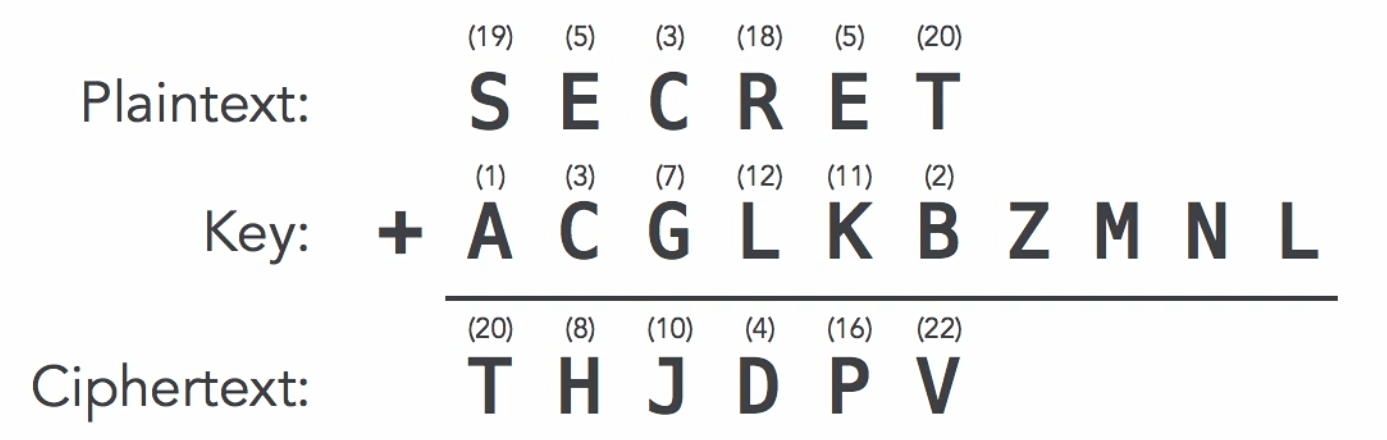

Encrypting the Message

Both the sender and the receiver use pads filled with random letters that are identical.

- The pad must be as long as all the messages exchanged.

- A page from the one-time pad might look like a series of random letters.

To encrypt a message, you write the plaintext on the pad. For example, take the word "secret." Each letter of the message is combined with a key letter from the pad, treating letters as numbers (A = 1, B = 2, etc.).

- Encrypt S by adding A (1) to get T

- Encrypt E by adding C (3) to get H

- Encrypt C by adding G (7) to get J

If the total goes past Z, wrap around the alphabet. For example, adding L (12) to R loops around to become D.

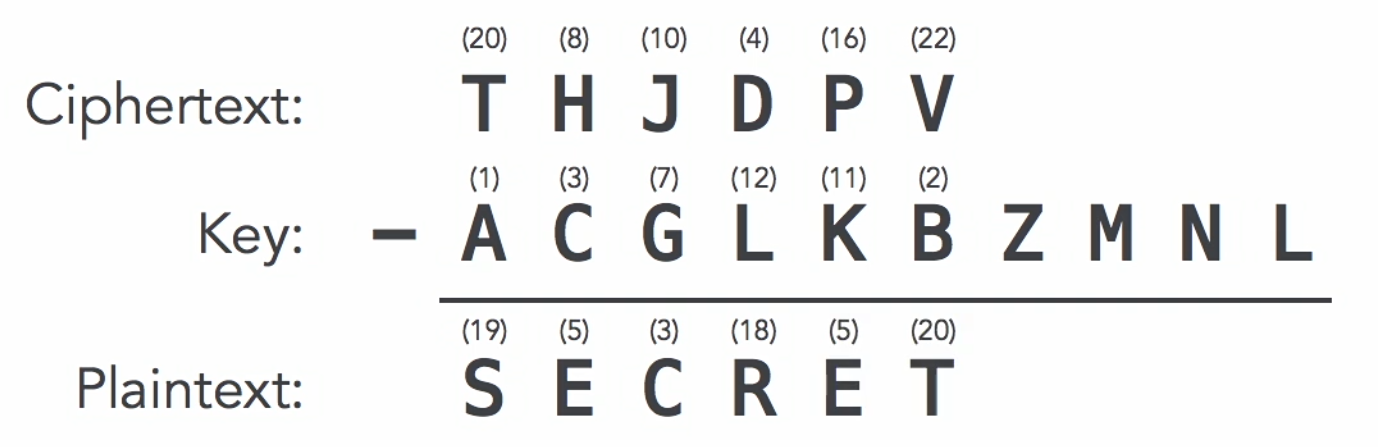

Decrypting the Message

To decrypt, the receiver subtracts the key letters from the encrypted message:

-

Start with the encrypted text: T, H, J, D, P, V

-

Subtract the matching key letters to recover the original message:

- T minus A = S

- H minus C = E

- J minus G = C

If the result goes before A, wrap backward through the alphabet. For example, D minus L loops back to R. Continue until you reveal the full message: "Secret."

Challenges

Despite its perfect security, the one-time pad isn't commonly used due to practical issues:

- Both parties need to exchange pads in person to maintain security.

- They must meet again when the pad pages are used up.

- This makes it inconvenient for frequent exchanges.

While the one-time pad offers perfect encryption, these challenges make it less practical for widespread use today.

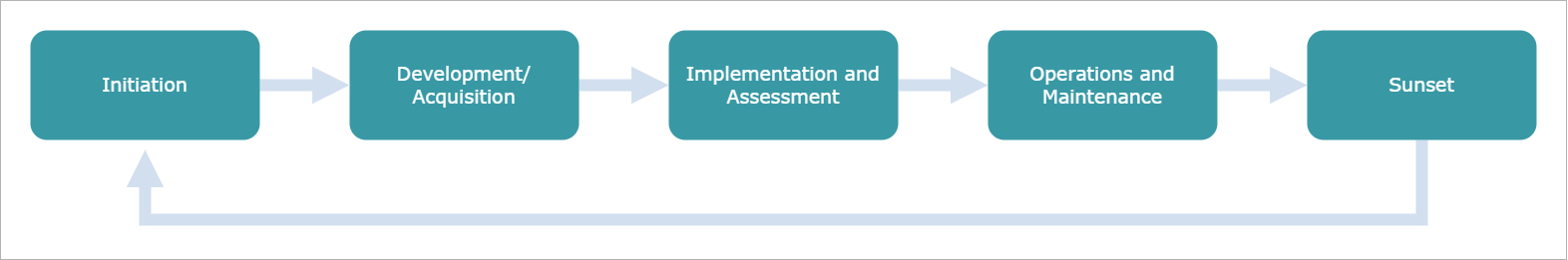

Cryptographic Lifecycles

Cryptographic algorithms and keys protect information, but they must be managed throughout their lifecycle to keep up with evolving threats.

Over time, some algorithms weaken due to flaws or short key lengths. A lifecycle approach ensures outdated methods are replaced, keeping systems secure.

NIST’s Five-Stage Lifecycle

-

Initiation

- Identify the need for a cryptographic system

- Define requirements based on data sensitivity

- Consider goals of confidentiality, integrity, and availability

-

Development / Acquisition

- Build or obtain the system

- Select proper software, hardware, and algorithms

- Generate and manage cryptographic keys

-

Implementation and Assessment

- Configure the system for use

- Test and evaluate against security requirements

- Fix issues before deployment

-

Operations and Maintenance

- Use the system in daily operations

- Monitor for vulnerabilities and threats

- Update or patch when needed to stay secure

-

Sunset

- Retire the system when it is no longer secure or needed

- Properly dispose of sensitive data and keys

- Transition to newer, stronger solutions